New research suggests Trump’s election could drive international MBAs to other shores

For the last five years, Indian students at all university levels have opted against studying in the U.K. at about the same rate they have chosen to go to the United States. This titanic 60% shift has been felt more keenly in the U.K., with its smaller overall higher-education population — and that was before last year’s Brexit vote made it likely that post-graduation employment and immigration opportunities will become even more restricted, thus making the Britain even less attractive for potential students.

But then the U.S. elected Donald Trump president. And one scholar who has crunched the numbers thinks that might be a game-changer for Indians — and for other international students, as well.

“India as a market is very focused on master’s-level programs, and if the U.S.’s immigration policies become negative and visas and all those things come under a much stricter policy of review, that can really make it unattractive to a lot of students, especially those from India who are looking at this as part of the cost of investment,” says Rahul Choudaha, principal researcher and CEO of DrEducation, a New York-based global higher education research and consulting firm.

SHARP CONTRASTS IN U.S., UK TRENDS

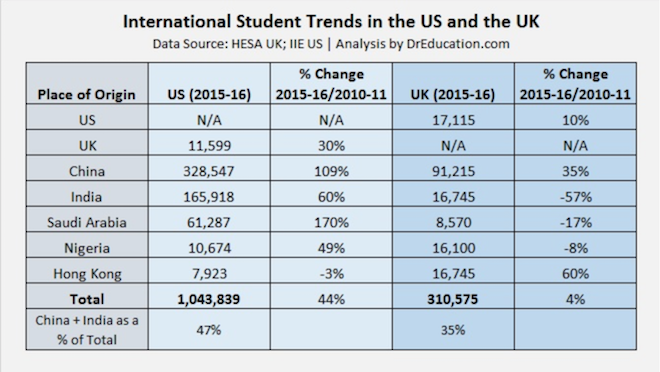

Since 2011, the overall Indian student population in the U.K. has fallen by 57% to 16,745, Choudaha says, while at the same time growing in the U.S. by 60%, to about 165,918. In other words, there are now 10 times as many Indian students studying in the U.S. as in the U.K.

Choudaha compiled his figures from recent reports by the U.S.-based Institute of International Education and Britain’s Higher Education Statistics Agency. He tells Poets&Quants that while both nonprofits have done extensive studies of their nations’ internal education landscape, no one has published a comparison of the two countries to get a clearer picture of the shifts in international student mobility.

(Unfortunately, Choudaha says, while we know that in the U.S. one of every five international students is enrolled in a business/management program — with the numbers increasing across all levels by 36% (145,514 to 197,258) from 2010 to 2015 — in the U.K. there is no available breakdown by the field of study for international students.)

TREND: SLOW OR NEGATIVE GROWTH FOR UK SCHOOLS

Rahul Choudaha

When Choudaha made his comparison by matching the U.S. and U.K. by level of education, definition of programs, and year of enrollment, he says he was surprised to see the gap between the decline of Indian students in Britain and the growth in the U.S. But there was more. He found that India is one of four places of origin where the U.S. and U.K. have seen sharply contrasting trends: there also has been a big shift in students from Saudi Arabia (+170% in U.S., -17% in UK), Nigeria (+49% in U.S., -8% in UK), and Hong Kong (-3% in U.S., +60% in UK).

Both the U.S. and U.K. have seen growth in their Chinese student populations, meanwhile, but the U.S. growth rate far outstrips that of the U.K. — 109% to 35%, respectively.

“The biggest challenge for British universities is that its top two source countries — China and India — are not driving the enrollment growth,” says Choudaha, who teaches at New York’s Baruch College and who has been blogging at DrEducation for about eight years, primarily looking at international student enrollment trends and their experiences. “These two countries account for over one-third of the total international student enrollment in the country. For the last four years, the overall enrollment for China has grown at a much slower pace compared to the U.S., while India has been experiencing a consistent decline.”